Animal Crossing has always been an important part of my life. It was magical and transportive at a time when things were dull and isolating. Like many American kids growing up in a small town, I adored AC because it offered me friendships unlike any others I had in real life. It also gave me Baabara, my first hag and an indicator of things to come.

My BFF Baabara seemed to have her own life and schedule (even if she didn’t). She had opinions about our neighbor named Bitty, about me, and about the town we all lived in. Sometimes a fashion craze would start and everyone would wear Baabara’s clothes, but each villager had their own combination of favorite furniture and a distinct personality type. While there were only really a few options that made up each villager, they intersected in ways that felt organic and real. My snooty friend Baabara really didn’t jive with Jay, who was all about fitness. Amidst their squabbles and pep talks, I felt like I belonged in the strange little town of animals. Everyone was debarbed, defanged, and declawed. Lions talked to deer. Birds joked with frogs. It was charming and safe.

Even with its high valley walls and defined list of activities, Animal Crossing felt limitless and full of choices. From the very beginning, you’re ushered through decision making. You answer innocent questions that later define your very appearance. You’re given (well, sold, really) a small home and propelled into ownership through a charming loan simulator. No one asks any questions of you. Why are you the only human? Why are you in this town? How can you communicate with these animals? What are the implications of this strange animal village nestled inside an obstructed valley?

And through this mystery—a child’s tabula rasa—AC gave us tools by which to discover ourselves. You could design your own home and clothing and essentially terraform the village with fruit-bearing trees. The ocean ebbed endlessly, shoring up sharks, sunfish, and seashells. A river cut through the valley, teeming with fish. There was an inexhaustible list of furniture themes you could mix and match while gaming the invisible Feng shui of your home. Every stylistic choice you decided upon would engrain itself into your unique world. And when you got bored of it, you could wipe it away and make something new. It was the Etch A Sketch of early 2000s gaming. Later iterations of the game would maximize on this creativity and even allow you to be the mayor, giving you absolute control over the iconic features and geography of your town.

Our lizard brains were happy because everything was collectible. Furniture, fossils, insects, fish, even the villagers themselves. Everything was part of an extensive index of items that could be—nay, needed to be—collected. If you were like me and had siblings, you probably fought over the game console on some summer mornings because you wanted to snatch up that day’s few available fossils.

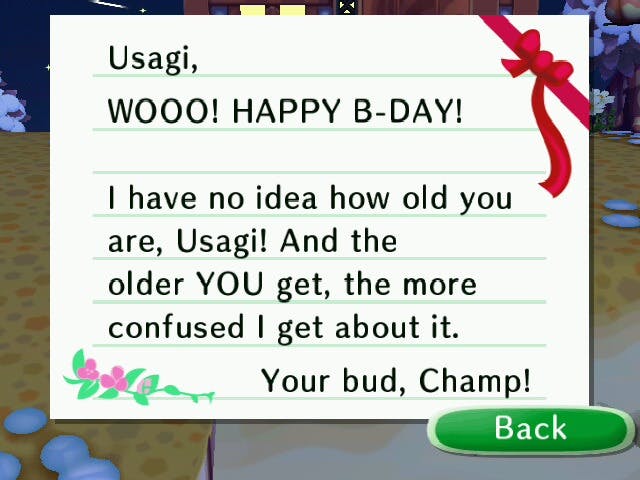

The beauty of Animal Crossing was in the clockwork motion of the mysterious village. Following our world in real time, the landscape blossomed through seasonal colors and celebrated holidays just like ours. In 2017 it’s hard to emphasize just how revolutionary this concept was. This type of technology was never seen before in a game. If I didn’t play for days or weeks, I’d find the village in a dilapidated state, scattered with weeds. Baabara would first poke fun at me, but then ultimately admit she missed me. Sometimes she got mad. Near the end of my time playing the game, Baabara was always mad at me, angry that I didn’t make time for her like I used to. And one day, she moved away. I still remember the stinging letter she sent, claiming she felt abandoned by our friendship. The fact that this Nintendo game made me feel guilty about my relationship with a digital sheep was so confounding that the implications of it (clearly) still affect me over a decade later. These villagers were real, and they were my friends. They wrote me letters, gave me presents, and asked me for advice. The interactions never felt one-sided. If anything, I felt like I owed them something.

In America, we’re raised on the conservative concepts of family and community. Released in America only a year after 9/11, AC came into our lives at a very different time. The pillars of democracy and free press were far from the peril they’re currently experiencing. Because social media was still on the horizon, the internet was a quieter and (arguably) less hostile place. Animal Crossing splashed into this quiet scene like a cannonball. Everyone in my school was addicted to Animal Crossing, or was getting a GameCube just to play it. This happened in many schools across the US, not just mine.

Fast forward to the hellish year of 2017. I’ve been playing Animal Crossing: Pocket Camp, Nintendo’s latest foray into mobile gaming, with all of these things in mind. In a year with a news cycle as loud as ours, Pocket Camp was barely a splash on the radar. At no point were we expecting a full port of the same quirky features and charming tasks from the original game or its sequels, but what’s on our phones now is markedly different from what used to be on our TV screens and Nintendo handhelds.

Do not be fooled. These are not our friends from the past.

It’s impossible to know where things went wrong. Pocket Camp is not a main title, it’s a spin-off, but it’s hard to even call it a spin-off. What we’ve been given is essentially a storefront hustling nostalgia.

Immediately upon launching the game, everything feels eerily familiar. The spinning title, the prompt to start. It tricks you with familiarity, but everything feels simplified. Instead of answering questions, you choose your character’s features outright. Soon you’re dragged through a dialogue sequence (a trademark of these Nintendo games) before ushered into an area that looks just like an Animal Crossing village. You’re finally home, you think. But wait… Something is still off. You’re admiring the gentle curvature of the horizon (another trademark) when suddenly, they appear:

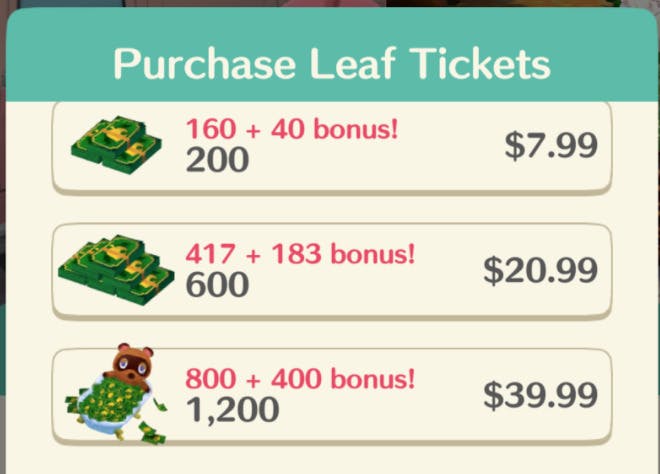

Ladies and gentlemen: late capitalism stole Animal Crossing from us. This banner space immediately sets the tone for what becomes a series of nudges to prepare your credit card: an aggressive log-in reward, a sudden pile-up of plainly named crafting materials, bag limits, time requirements, and locked areas. Essences, bells, and Leaf Tickets (kaching, kaching, baby) blend together as the rewards pile on quickly and frequently at the beginning. The game rewards you for anything and everything at first, and it feels bountiful. Soon these rewards come to a trickle, then they dry up. You can feel Nintendo trying to hook you on this new experience like a drug. Shaking trees remains familiar and yields fruit, but immediately afterwards a countdown appears until the next harvest, which becomes a constant reminder of your newfound slavery.

That’s right: slavery.

What used to be surprise gifts for your friends has transformed into a list of demands. Your house has been replaced with a tiny camper and a small plot of ground you can customize in the middle of the forest. There is no roof. While you no longer have a village to roam freely, you can zip from locale to locale (beach, lake, forest, and island) scooping up the very few bugs, fish, and fruit that litter the map. The navigation style works well on the phone, but the challenge bleeds away with how accessible it is. Fishing and catching bugs have never been this easy. There are only a few of each type so there’s no real reward for collecting them. We’re allowed to sell them to our friends online via market boxes, but there’s little incentive to buy these items from your friends because it’s so easy to catch them yourself. The museum has been replaced with daily tasks to encourage you to log in and find particular items. As other villagers move around the locations via campsites, they make requests for these same items which appear on your map. Give a villager what they want, and their friendship level will go up. Once their friendship level reaches a certain point, you can invite them to come to your campsite.

This means they’ll essentially be on your “home turf” every time you open the app to play, and will be easily accessible to chat with. However, before you can invite them you must craft their required furniture. Up until now the game just feels shallow, but it’s at this point that it just starts to feel… dirty. This is the bait and switch, ladies and gentlemen.

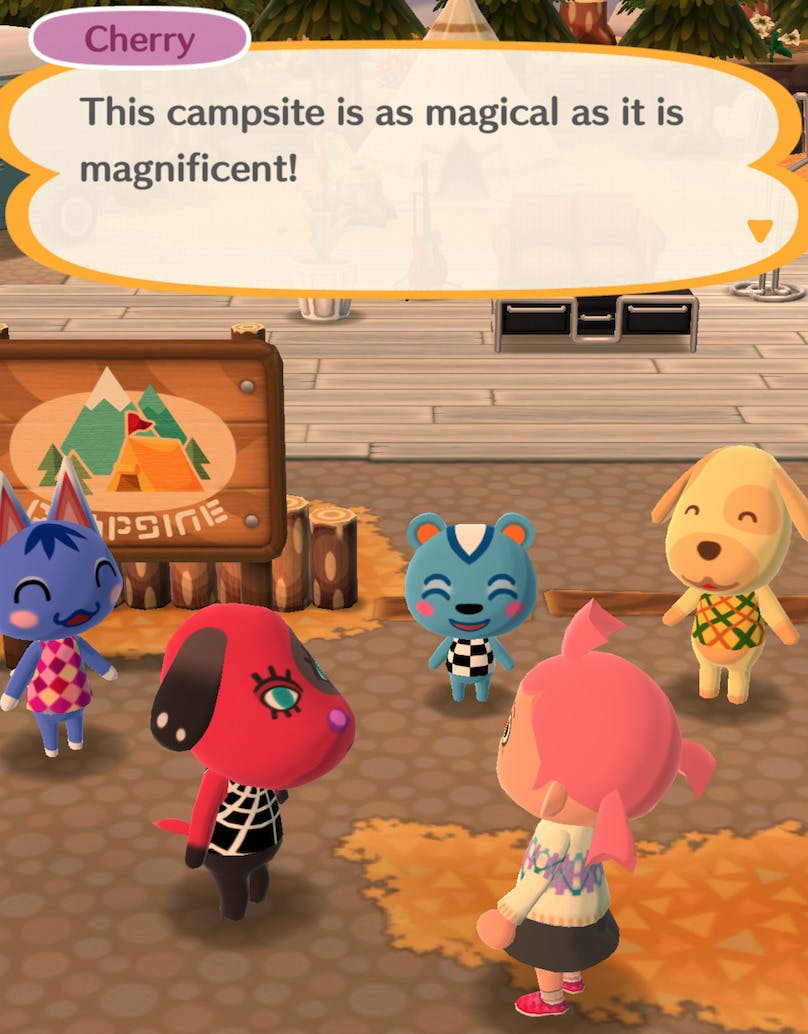

Once you finally build their friendship level and construct their furniture (either by waiting or by spending Leaf Tickets, [kaching, kaching, baby]), you’ll welcome them to your campsite with an utterly bizarre montage that is maybe cute in some instances but overall comes across as just a weird montage of consumerism. The video clips of my childhood friend Butch rubbing his doggie butt on my furniture didn’t excite me about our reunion. It just reminded me of the invisible hand behind it all, using Butch’s nostalgic shell (AKA his model and texture) to try and sell me fake animal money.

Once this identity-destroying cutscene is over, these villagers are just props. The personalities of our old friends have been bleached away. You wonder if the real ones are back in your original village somewhere, and if these are eerie doppelgangers, motivated only by greed and flagrant narcissism. They discuss (in vague words) their lives offscreen and back home, but there’s no real reflection on the time and space you two occupy. They don’t react if you ignore them for a few days. There’s nothing else to do in this space except serve them and their needs. These new animal overlords feel flat and their once-dripping charm barely perspires from the dialogue. You spend all of your conversations asking what they want, giving it to them, or being rewarded for it. There are only a few villager types and they all repeat themselves in this transaction with very little variance in dialogue. Even as they strut around your campsite, sit on your bed, drink a soda by themselves in the corner, or dance, they feel like puppets tracing clockwork animations on a stage. They’re all interchangeable beyond maybe one token element of their personality, and the charm evaporates.

Sometimes after completing a task, the villager will use the items you gave them to act out a quick bonding cutscene. These are surprisingly varied, and range from smoking fish to baking a cake to making shell jewelry. My favorite involved painting butterflies that I had just collected. It’s moments like this where Pocket Camp shines and I feel—just for a moment—like my old friendships are returned in full, and I wish we could’ve done things like this in the original game.

But soon these cutscenes end and the storefront returns. Nintendo seems to have taken a lesson from Tom Nook when designing this game. Or maybe Tom Nook (who is mysteriously absent from the game except via—you guessed it—a premium item) is behind all of this. In the store menu, you’ll find him bathing in a literal tub of money.

Either way, everything in this game is fluffing you up for a microtransaction, and the experiences comes across as thin. I know this is a free game and premium experiences are necessary to fund its creation, but I would’ve gladly forked over $5 (or even more) upfront for a more thought-out and complete experience without paywalls.

I think we, as mobile gamers, need to come out of this mindset that we don’t want to pay upfront for phone games. I think when we were younger it was easier for our parents or financial guarantors to say “no” to purchasing what is essentially data, but times have changed and we pay money for digital services, experiences, and goods all the time now. This blocking attitude we harbor towards apps is what fuels the creation of microtransaction games, because studios have to hedge their bets in order to recoup development costs.

There were several missed opportunities here. We could’ve had access to our old friends on an entirely new level. Imagine if there was a social network inside the game, and these villagers could message you an each other throughout the day. Our character is already given a snazzy smartphone that pops out when you open the menu (a cute touch), so it wouldn’t feel out of place. These villagers could have the capacity to befriend even each other and weave together to form a social fabric beyond their current static forms. While the camping aesthetic is nice, it feels lazy because it allowed Nintendo to heavily recycle their past assets. I think a city setting could’ve opened more opportunities for new gameplay and interactions.

Up until now I haven’t really touched on the multiplayer experience of this game, and it’s because that element of the game ultimately feels like an afterthought. When you travel from place to place in the game, sometimes you’ll see other campers pulled up in the area, and another human milling around. These could be people from your friends list, but often it’s strangers from around the world. I bumped into several Japanese and Spanish names while playing, and while it was interesting at first to visit their camps, this experience understandably felt like a diluted version of New Leaf’s passing friend exchange system. There’s really no incentive or reason to visit someone else’s campsite except to give them kudos, which is sometimes a daily task. This makes your own received kudos feel fake and forced, because you can assume that person only sent you a kudos because they needed to hit a quota that day.

I strongly believe that for many people, Animal Crossing is a peaceful escape from anxiety and stress in our daily lives. Neko Atsume is a mobile experience that people have frequently discussed in regards to its anxiety relief. Part of me was hoping that Pocket Camp would follow this same vein and become the crown jewel of mobile phone escapism, but it’s hard to relax in this purchase-o-rama. When will a mobile game finally break this cycle of microtransactions? Only when we, as a community, are more comfortable buying app games upfront instead of forking over money down the line. Our taste-but-not-buy mentality is sinking our prospects at quality handheld fun, and it’s up to us to stop it. The saturation of late capitalism has ingrained a basic formula for making money from an app, and microtransactions are the foundation of this business model.

My screen time on the game has decreased day by day since its release, but feel free to add me, Mean Tammy, to your friends list and help me go to the mines. Because like most things in this game, there’s a barrier to entry and you have to be either rich or popular to get there. When did Animal Crossing start to so sickly mirror our world?